I’m staring at the cursor on my laptop screen, instantly regretting the words being typed by my fingers. My assignment today is to write about Arnold Palmer’s legacy, but I loathe the concept. After all, a legacy is a lasting contribution from a person, conceived as a testament to their honor. It’s also an insinuation that their legacy is cemented, that they are done, that soon enough even the most immortal souls among us will meet their own mortality and just like that, they’ll be gone.

I don’t want to write about Mr. Palmer’s legacy, because that would be an admission that he will someday be gone. And I’m not ready for that. Not many of us are.

By the way, it’s always “Mr. Palmer.” Sure, when writing about his sublime historical record and everything he’s meant to the game of golf, the surname “Palmer” will suffice; and yes, when speaking tangentially of his quick wit and mass appeal, a rhapsodic summoning of “Arnie” is patently acceptable.

When speaking with him face-to-face, though, when asking a question about the good ol’ days or engaging in a colloquial conversation about the weather, he is always, without fail, addressed as “Mr. Palmer.”

I wish I could understand it. I’ve never called any boss I’ve had Mr. anything. When I run into old junior high teachers who implore, “Call me Fred,” I accept their offer. I’ve started interviews of Jack Nicklaus with the words, “So, Jack…” and I’ve started friendly chats with Gary Player by crowing, “Hi Gary…” I don’t know why. They are no less honorable than Arnold Palmer, no less approachable or influential or legendary.

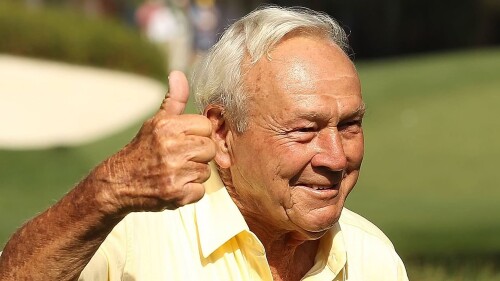

It’s not as if Mr. Palmer demands it, either. The reality is, with so many people acting so reverentially toward him on a daily basis, you get the sense that the boy from working-class Latrobe would rather be addressed as, “Hey, buddy…” or even something more playfully disparaging. Anyone want to take a guess on the number of times a stranger mistakenly called him “Arnie” and he scolded them by replying that he’s “Mr. Palmer”? Chances of that ever having occurred are exactly zero percent.

Click on the title or the image below the title to read all GolfChannel.com “Arnie” articles.

The last time I saw him was a few months ago at Bay Hill Club & Lodge, his Orlando home for nearly a half-century. He was camped out in his golf cart, just left of the first tee. A poet might proclaim that it was an image of the King presiding over his court, but that would be too eloquent. It was, simply, Mr. Palmer in his element – surrounded by the faint scent of freshly mown grass on a nearby fairway and the unmistakable sound of a faraway tee shot struck too close to the toe.

Along with some colleagues, I approached him. White hair wispy in the breeze, friendly smile across his face, he asked if we’d enjoyed playing the course that day. “Yes, Mr. Palmer,” we all answered in unison, four grown men instantly reduced to wide-eyed schoolchildren in his presence. We posed for photos with him – I’ve got about eight or nine now and keep adding to the collection, because, well, why wouldn’t I? – and each of us ended the encounter with a hearty handshake and a “Thank you, Mr. Palmer.”

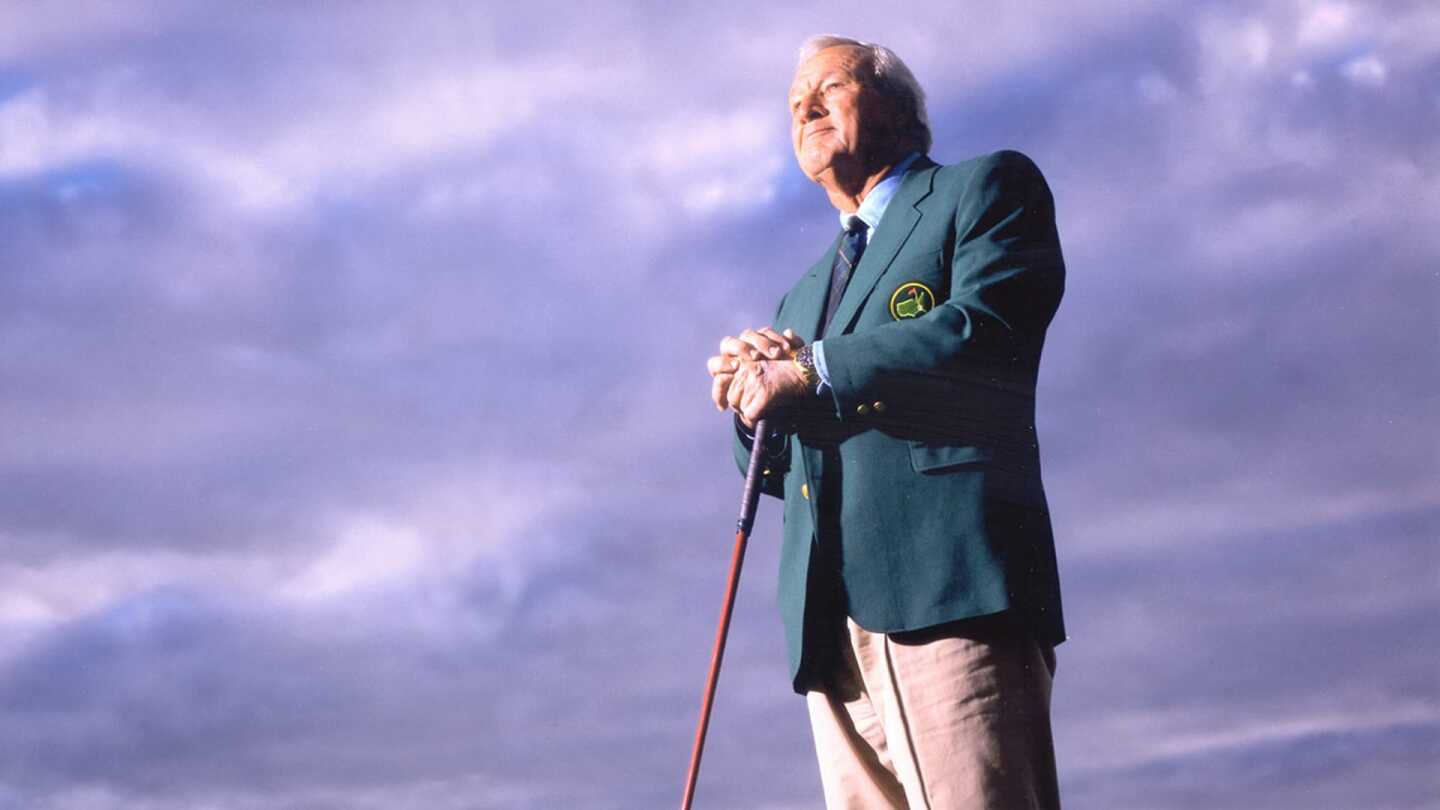

Within a few minutes, he drove the cart – the one with two bags on the back, both his – about 30 yards, over to the far right side of the Bay Hill driving range. A bucket of balls at his feet, he proceeded to execute that familiar lash through each one. It was no longer his powerful horsewhip of the 1960s; he struggled to make a full rotation in his backswing and the ball hardly exploded off his clubface. After about 10 minutes, he rested, leaning on a mid-iron like a cane. The look on his face read pensive, but I could have sworn it was only masking his disgust.

Maybe this is his legacy, I thought. Maybe the lasting impression he’s left on all of us is that we can never stop improving, that even decades removed from our greatest triumphs, we can still dig for secrets in the dirt on a random overcast Wednesday afternoon.

This is the part I loathe thinking about, and loathe typing even more.

Mr. Palmer shouldn’t have a legacy yet, because he isn’t done. He isn’t finished swapping stories on the first tee, isn’t finished beating balls into the cavernous sky.

That’s the assignment, though, and so even though my mind wanders elsewhere, to thoughts of a world in which he remains immortal, forever trying to improve his swing, my fingers keep typing thoughts I don’t want to think about.

He’ll be remembered for his records, of course – and just in case he isn’t, Wikipedia will always be around to remind us that he won 26 times as an amateur and 95 times as a professional and seven times in a major championship. Those numbers – some of them, at least – pale in comparison with the likes of Nicklaus and Tiger Woods. He wasn’t the greatest to ever play the game, and yet he might be golf’s career leader in being spoken about in hushed tones, on the same leaderboard with Old Tom Morris and Bobby Jones and Ben Hogan.

He’ll be remembered for his hospitals – those bearing both his name and that of Winnie, his late first wife. Every day, in actions of obliviousness that would leave a golf fanatic incredulous, patients walk through these front doors with no knowledge of Arnold Palmer and his importance within the game’s foundation. They only know this as a sanctuary where they are healed or consoled or bring a new life into the world. Thousands of parents can proudly claim their children were born “at Palmer” – and if that’s not reason enough for a legacy, then nothing is.

He’ll be remembered for his eponymous drink – three parts iced tea, one part lemonade – that caught on when he first special-ordered it in a Palm Springs clubhouse while designing a golf course there. I know, it doesn’t have quite the significance of historical achievements or building hospitals, but let’s recap: The man has a beverage known worldwide by his name. That’s the stuff of Roy Rogers and Shirley Temple. Oh, and to answer the question he’s been asked a million times before: When he orders one these days, he just asks for a Palmer.

He’ll be remembered for all of these things, but when other greats of the game – his peers – are asked about his legacy, they all point to his influence on the game he loves.

“Arnold’s legacy is that people followed him, people adored him,” Nicklaus says. “He was probably the most popular person to ever play the game.”

“He stimulated the interest in the average person and the companies in supporting golf,” explains Billy Casper. “It wasn’t until he started really thriving and being successful in the late ’50s and ‘60s that golf really took off.”

“Listen,” Lee Trevino implores in his inimitable drawl. “Let me tell you what his legacy is: Every one of these kids that are playing today should have Arnold Palmer’s picture in their house and kiss it every morning. That’s it.”

They’re right, I know. They’ve nailed it, in more introspective terms than I could ever hope to produce. They know it because they lived it. They witnessed the era before he placed his personal stamp on the game; and the one during his heyday, when golf transformed from a country club activity to one the masses watched on television; and the one we’re currently entrenched in, where everything elite pro golfers do – from their swings to their interviews to their involvement with fans – is colored by what’s been passed down through generations by the man they still refer to as Mr. Palmer.

The cursor is still blinking. I’ve written this much and still don’t have an answer for why a man known simply as “Arnie” to millions of adoring fans is called “Mr. Palmer” whenever he’s addressed. Sure, respect and reverence have plenty to do with it, but we respect lots of people who don’t receive such honorary treatment.

There’s something bigger about him, something intangible that can’t fit onto a Wikipedia page.

It’s not just his record as one of the all-time greats, nor is it his influence on multiple generations in the game. It’s bigger than golf. Bigger, even, than the hospitals in his name and the drink that will endure long after he’s finally proven to be mortal. Maybe it has something to do with the man I witnessed that April afternoon, beating range balls into the sky, hoping to recall a trick or two before his 85th birthday.

More than likely, it’s all of these things together.

Whatever reasons we have for calling him “Mr. Palmer” all these years, that’s his legacy. I just loathe thinking about it, because I don’t want to believe that he will someday be gone.