It’s an interesting debate: What made Arnold Palmer a transcendent figure not only in golf, but in sports?

The easy answer: It was the whole package.

He was the handsome leading man with the hard-charging swing and blue-collar background who came along at just the right time when televisions were sprouting up in living rooms around the world.

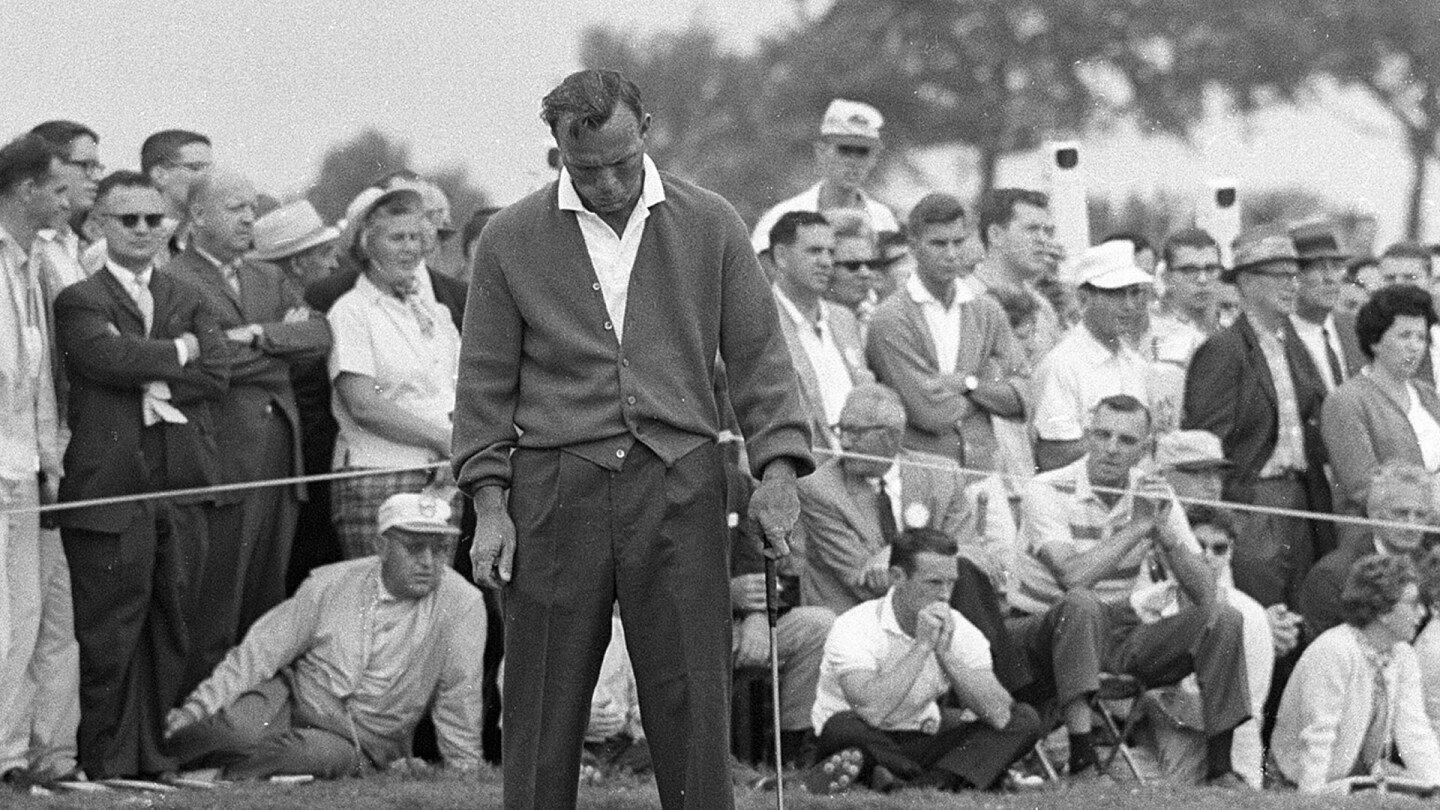

But one ingredient that is often overlooked in this perfect superhero recipe is that, sure, Palmer won big (seven major titles, 62 PGA Tour wins), but he also lost big.

“Arnold was majestic at winning and losing,” said former player and longtime golf announcer Peter Alliss.

His flair for the dramatic often resulted in oh-my-gosh-did-you-see-that?! victories (see, 1960 U.S. Open), but could also result in how-in-the-world-did-he-lose-that-big-of-a-lead?! collapses (see, 1966 U.S. Open).

For all of the heartbreak Palmer caused himself, he often felt worse for his adoring army of fans, knowing that they had pushed him so hard to win, only to see their hero come up short in the end.

Palmer was always a man of the people, even in defeat.

“The minute his car pulled into the drive the neighbors would arrive,” said Amy Saunders, Palmer’s daughter. “It was a ritual, they all came. And I think it was a great opportunity for him to be able to unwind and share a lot of that with them. You know I think probably (sister) Peg and I first felt a little bit as though we wanted his time, but now in hindsight I realize how important that was for him, but also good for us because he could share with them and vent all of the frustrations of the week or the highlights of it. We were always included. It wasn’t like we were excluded from it, but it was a gathering of adults and he would come home and they would enjoy sitting together and talking and reflecting on the week.”

What’s even more intriguing about Palmer’s career arc is that some of his jaw-dropping collapses happened during his prime, not when he was an inexperienced young gun.

At the 1961 Masters, Palmer was leading Gary Player by one stroke and his ball was sitting pretty in the 18th fairway. Palmer was about to win his third green jacket in four years and become the first man to successfully defend at Augusta.

But Palmer got caught up in the moment (he accepted congratulations from his friend George Low while walking to his drive on 18), and he forgot an important lesson his father, Deacon, had drilled into him – don’t ever get ahead of yourself.

Palmer’s second shot sailed into the right greenside bunker, and before he knew it Palmer was tapping in for a double bogey to hand Player his first green jacket.

Click on the title or the image below the title to read all GolfChannel.com “Arnie” articles.

It was a simple mistake at the worst possible moment. But other collapses would be harder to explain.

At the 1962 U.S. Open, Palmer was riding a huge wave of confidence. He had rebounded from his disappointing loss at the 1961 Masters by capturing his first claret jug at the British Open at Royal Birkdale.

At the 1962 Masters, Palmer had extracted revenge against Player by storming back in the final round to tie the gritty South African and Dow Finsterwald and force the first three-man, 18-hole playoff in Masters history. Palmer defeated both men handily the next day to capture his third green jacket.

Now he was the heavy favorite to win his second U.S. Open title, with the championship being held about 40 miles from his hometown of Latrobe, Pa., at Oakmont Country Club, just outside of Pittsburgh.

“He had visions of winning the Grand Slam,” said Rand Jerris, author, historian, and USGA director of communications. “He knew this was a real possibility for him this year, and he knew given the emotional benefits, the excitement, that Oakmont was going to bring out the very best in his game.”

Palmer was in control in the final round, but a fatal flaw was beginning to emerge – he wanted it too bad. He flubbed a chip shot on the par-5 ninth and wound up making bogey on a hole he could have easily birdied. Instead of extending his lead, Palmer gave a 22-year-old Jack Nicklaus an opening.

The soon-to-be Golden Bear didn’t have the added pressure of trying to win the biggest tournament in his home state with scores of friends and family members in the gallery.

“I went to Oakmont the week before the tournament … played a couple practice rounds, and I sort of felt going into Oakmont that that was my tournament, nobody else’s,” Nicklaus said. “I had finished second in 1960, fourth in 1961. I had a chance to win both golf tournaments, didn’t do it , and I really liked what I took from the practice rounds, and I said this is going to be my week.”

Nicklaus took advantage of Palmer’s mistake with birdies on Nos. 9 and 11, and after Palmer missed a 10-foot birdie putt on 18 to win, the two leading men were heading to an 18-hole playoff on Sunday.

Palmer bogeyed the first hole of the playoff and played catch-up the entire round. He made a mini-charge with birdies on Nos. 9, 11 and 12 to cut Nicklaus’ lead to one, but then he three-putted the par-3 13th and eventually lost by three strokes.

Arnie’s Army was stunned.

A stone-faced kid from Columbus, Ohio, who had never won a PGA Tour event, marched right into Palmer’s backyard and took down a five-time major champion.

Unlike Palmer’s previous heartbreaks, this was personal.

It hurt Palmer that not only did he let down his army, but that those same fans treated Nicklaus with disgust.

“The fans at Oakmont were not your typical golf fans,” Ian O’Connor, author of “Arnie & Jack,” said. “These were blue-collar, Pittsburgh people. They were Steelers fans. They were rowdy and they were stomping the earth when Jack Nicklaus was putting.

“Nothing was out of bounds in terms of trying to throw Jack Nicklaus off his game,” O’Connor said. “They were calling him ‘Fat Jack.’”

Oh, there was more.

“They held signs that said ‘Jack Hit It Here’ when they were standing in the deepest rough on the golf course,” Jerris said. “We think about golf as this dignified, quiet sort of game, and the galleries at Oakmont were anything but that. They were true die-hard Pittsburgh natives who were pulling for their native son. They were going to give Arnold that advantage, and if it meant taking Jack down a little bit, they didn’t seem very hesitant to go in that direction.”

Their jeers and rude remarks were supposed to crush Nicklaus’ spirit, but instead they had the opposite effect.

Palmer was embarrassed. The fans showed little class, and it certainly wasn’t the way he wanted to try to win his second U.S. Open. Nicklaus’ father, Charlie, was in the crowd and was equally upset. At one point, Ohio State football coach Woody Hayes, a family friend of the Nicklauses, had to restrain Charlie from going after a boisterous member of the gallery.

The only person it didn’t seem to bother was Nicklaus.

“It never did register,” Nicklaus said. “I mean that’s the phenomenon everybody can’t understand. ‘How can you not hear the gallery?’ I say, ‘I was playing golf.’ I paid no attention to anybody. I wasn’t interested in that.”

The 1960 U.S. Open is Palmer’s career-defining moment, but the championship would soon also be part of his stunning Rolodex of gut-wrenching major-championship losses. Starting with the playoff loss to Nicklaus in 1962, Palmer also lost playoffs in 1963 (Julius Boros) and 1966 (Billy Casper). Palmer would also finish second to Nicklaus by four strokes in 1967.

It was that overtime defeat to Casper at San Francisco’s Olympic Club that will go down as one of the biggest head-scratchers in major championship history.

Much has been made about Greg Norman blowing a six-shot lead starting the final round at the 1996 Masters. Palmer blew a seven-shot advantage with nine holes to go.

Just like when he was standing in the 18th fairway at the 1961 Masters, Palmer got ahead of himself and forgot to take care of business. Instead of keeping his focus on playing the course, Palmer felt he had the tournament secure and now he wanted to beat Ben Hogan’s U.S. Open record of 276. Palmer and Hogan were never buddies, and now Palmer had a chance to erase one of Hogan’s hallmark records in the tournament that defined the Hawk’s legendary career.

Once Palmer lost his focus, his lead quickly evaporated.

He was still five shots ahead of Casper with four holes to play, but Palmer bogeyed the par-3 15th and Casper made a birdie.

Now he was three up with three to play.

At the par-5 16th, another two-shot swing.

One up with two to play.

Palmer recorded his third consecutive bogey when he left his par putt inches short at the par-4 17th.

All square with one to play.

Both players made par at 18, and they headed to an 18-hole playoff.

The next day Palmer shot a 73 to lose to Casper by four shots.

“It was really devastating to him, because some of his friends are my friends and many of them said that he was never the same after that,” Casper said.

Said Palmer’s daughter, Peggy: “It was very hard, and knowing that he was going to come home … after Olympic, I’ll never forget that. It was sickening.”

The U.S. Open provided Palmer with plenty of stinging defeats, but he at least he could always hang his visor on his thrilling win in 1960.

The PGA Championship, however, also provided plenty of heartbreak - but no victories.

It’s the gaping hole in Palmer’s resume.

“No question, not winning the Grand Slam, not winning the PGA Championship, keeps Arnold slightly down among the all-time greats,” Jaime Diaz, Golf World’s editor-in-chief, said. “I mean, it’s just unfortunately the reality of, you know, compiling a record and it’s a hole on his record. It was always so sad when he didn’t win the PGA because he came very, very close.”

Palmer had no doubt he would one day capture the PGA. He even admitted in his autobiography “A Golfer’s Life,” that he kept a spot reserved for the Wanamaker trophy in his display case.

Palmer finished in the top 10 six times at the PGA, and three times he finished tied for second.

Instead of being among the men who have won all four modern Grand Slam events – Gene Sarazen, Hogan, Nicklaus, Player and Tiger Woods – Palmer is part of the group of players who completed three of the four legs of the career slam – Tom Watson (PGA), Raymond Floyd (British Open), Lee Trevino (Masters), Byron Nelson (British Open) and Sam Snead (U.S. Open).

Palmer won his last major at 34, a time when a lot of players are just reaching their prime.

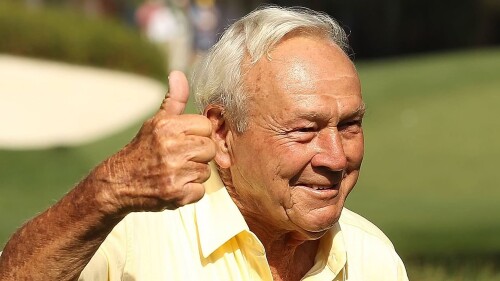

It’s often said you can tell more about a man during the tough times, and Palmer was no exception. After losing the 1966 U.S. Open, his most devastating of many painful defeats, Palmer honored a promise to a friend.

“He and Winnie flew from San Francisco to Colorado Springs where I had accepted a job two or three years prior, and we had dinner with the president of the hotel and the general manager and their wives,” Finsterwald said. “The guy was so gracious. We had dishwashers coming out of the kitchen asking for his autograph, and he accommodated their requests. You would have thought he had just won the Open instead of having one of the low points in his career.”