The timing was superb. So good, in fact, that it wasn’t a fair fight.

Television in the late 1950s was in the midst of a phenomenal growth spurt. Only an estimated 9 percent of U.S. households had TV sets at the beginning of the decade. By 1958, the figure was almost 85 percent. Televised golf was expanding as well. From the modest beginnings of a single-station broadcast of parts of the 1947 U.S. Open and the first nationally televised tournament, the 1953 Tam O’Shanter World Championship, by 1958 televised golf included the Masters (only holes 15-18), U.S. Open (only the final day) and PGA Championship (for the first time).

What was missing, however, was a superstar, someone who could appeal to the masses, someone everyone could adore. The careers of the two winningest players of the postwar era, Ben Hogan and Sam Snead, were winding down. And though both men were supremely talented, they weren’t especially charismatic. Nor did anyone else in men’s professional golf have the right combination of accomplishment and – let’s be honest – sex appeal.

Until, at that precise time, along came a dashing 20-something who was infinitely cooler than the coolest person you know.

Arnold Palmer hitched up his pants before every swat, flicked away the cigarette that had been dangling from his lips and swung for the fences with a violent, corkscrew-type swing. He backed up his style with substance, too, collecting all seven of his major victories in a six-year span from 1958-64.

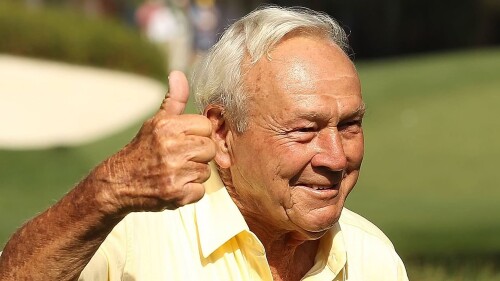

Click on the title or the image below the title to read all GolfChannel.com “Arnie” articles.

Simply, Arnold Palmer and television made an unbeatable pair. Everything about Palmer was irresistible to television cameras. Television cameras made Palmer larger than life. He quickly became everybody’s hero.

“Television was great for golf and Arnold, and Arnold was great for television. It worked both ways,” Jack Nicklaus said. “Arnold was flamboyant and exciting, fun to watch. People gravitated to him because he played these great recovery shots and that’s what people related to.”

“They were made for each other,” legendary sportscaster Jack Whitaker said. “Arnold would have been good anyway without television, but I think the combination – his personality and television – was a marvelous cocktail.”

The ingredients of that cocktail first were concocted in 1958 when Palmer dramatically won his first major championship at the Masters. He made eagle on the par-5 13th hole on the way to a one-shot victory. Palmer’s charm and presence were on display for a national audience that Sunday at Augusta National as the Masters was televised for only the third time. On that splendid Georgia day amongst the blooming azaleas Arnie’s Army was born.

“I was watching just like the rest of America, watching the Masters as a kid and obviously he was winning,” Ben Crenshaw recalls. “His fashion, the way he won and the way that he would play, it seemed like everything got caught up in his wake when he played.”

Two years later the legend grew exponentially. Having already birdied the final two holes to win the 1960 Masters by a shot, Palmer came from seven shots behind in the final round to shoot 65 and win his first U.S. Open.

Angered by a reporter friend’s comment before the final round that he had no chance to win, a steaming Palmer drove the green on the par-4 opening hole for an easy two-putt birdie, then chipped in for birdie on the second. In all he birdied the first four holes and six of the first seven.

That same year Palmer – on the basis of a handshake deal – agreed to be represented by friend Mark McCormack’s International Management Group, which would quickly become sport’s first super agency. McCormack sought to capitalize on his client’s good looks, modest background, affability and golfing prowess. The plan from the start was to turn Palmer’s total package into a global brand. In two years Palmer’s endorsement earnings skyrocketed from $6,000 per year to $500,000.

Interest in golf, particularly on TV, towered too.

“If it wasn’t for Arnold, the way he played the game and how he caught the imagination of the public, it would’ve taken the game many more years to have grown and gain the recognition that it gained under Arnold’s achievements,” Billy Casper said.

The complete list of those achievements is too vast to recount, and you likely already know the most significant accolades anyway. Just know that as Palmer’s resume continued to spike, so, too, did interest in the game.

“He was a blue-collar type golfer,” Jack Nicklaus said. “He won, but he was a good leader and a good champion and a good role model for the game. Had it been another guy coming along and wasn’t a good role model or didn’t handle himself well, I think that would have hurt the game.”

The King’s immense popularity for the first four decades of his career (1950s-80s) is a large reason why Golf Channel was launched nearly 20 years ago. Entrepreneur Joe Gibbs first hatched the idea of a 24-hour golf network in the early 1990s and shared it with Palmer.

Gibbs needed name recognition and instant credibility. He persuaded Palmer to buy into his idea and the duo secured $80 million in financing over the next couple of years. On Jan. 17, 1995, Palmer made the ceremonial flip of the switch to launch the network that now is available in more than 82 million homes.

“Gentlemen, if I hadn’t tried to hit it through the trees a few times in my life, none of us would be here,” Gibbs recalls Palmer saying at the meeting where Palmer was finally convinced that Golf Channel was something that could be sustainable. “After that, he was committed.”

Said Palmer: “I never thought I would sit and watch a golf program every day, day in and day out as I do now.

“A lot of people thought, ‘Well, that might not work’, but it has worked so well. To see what has happened here is certainly one of the great thrills of my life.”

Palmer has had many great thrills in his 85 years but has provided many more to those who have seen him both on the tube and in person. In both forms, Palmer has always moved the needle.

“I feel we were very fortunate to have the right guy come along at the right time,” Dow Finsterwald said.

And extremely fortunate that Palmer became best friends with television all those years ago.