The King doesn’t own the record for most major victories or most PGA Tour wins.

Six men – Tom Watson (8), Gary Player (9), Ben Hogan (9), Walter Hagen (11), Tiger Woods (14) and Jack Nicklaus (18) – have won more major titles than Arnold Palmer, and four – Hogan (64), Nicklaus (73), Woods (79) and Sam Snead (82) – have more Tour triumphs than Palmer’s 62.

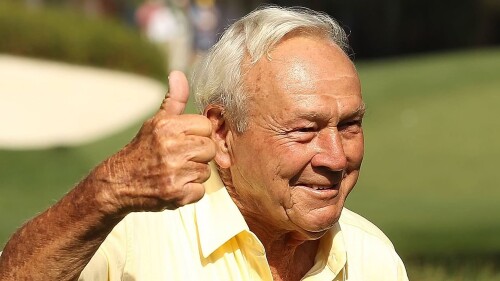

But when Palmer was done winning seven major titles in six years, he had changed the game forever. With his working-class background, GQ looks, homemade swing and heart-stopping victories, Palmer elevated the stature of golf’s major championships, and with the sport in its infancy on television, he gave the people watching at home something they didn’t have – a hero to cheer for.

Palmer began his magical run at the 1958 Masters. But it was four years prior, when he was just a 24-year-old amateur from Latrobe, Pa., that set the wheels in motion.

Life as a professional golfer was a risky proposition in 1954. It wasn’t a promising future of $10 million purses and private jets. But like so many things in golf, Palmer was about to change all of that.

Fresh out of a four-year stint in the Coast Guard – where he spent plenty of time daydreaming about resuming his budding amateur golf career – Palmer met a local paint rep named Bill Wehnes, who gave the young golfer the break he needed – a steady job as a paint salesman and the freedom to have afternoons and weekends off to get his game back in shape.

First, however, Palmer was supposed to return to Wake Forest and finish his business degree. He did return, but spent more time working on his game than on his degree. He left again for Cleveland, where he had been stationed in the Coast Guard, and soon had a pretty nice setup – sell paint in the morning, break for lunch, then play golf in the afternoon.

Honing his game at Canterbury Golf Club, a two-time U.S. Open site, Palmer’s confidence grew to a level he called “frightening” in his 1999 autobiography, “A Golfer’s Life.”

He set his sights on the 1954 U.S. Amateur, and soon his life – and the game of golf – would never be the same.

Click on the title or the image below the title to read all GolfChannel.com “Arnie” articles.

For many ams, winning the U.S. Amateur and having their name etched on the same trophy as Bobby Jones’ is the crowning achievement of their career. For others, an Amateur win is validation for dreams of a future life as a touring professional. After all, if you could survive the crucible of six 18-hole matches in four days, plus a 36-hole semifinal and a 36-hole final, then you might be good enough to step inside the ropes with the Hawk, Lord Byron and the Slammer.

Coming into the 1954 edition at the Country Club of Detroit, Palmer had yet to establish himself as a marquee name. Instead players such as Frank Stranahan (1948 and ’50 British Amateur champion), Harvie Ward (1952 British Amateur champion) and Billy Joe Patton (1954 North and South) were favored to win the Havemeyer Trophy.

In four previous trips to the Amateur, Palmer had made it only as far as the round of 16 (1953). But with his game back in tournament shape, he was ready to make a run.

His first three matches were nail-biters, but Palmer escaped from trouble every time. It would become a trademark throughout his career that would endear him to fans. In fact, nearly all the trademarks that would define his legend were on display at the Amateur: the go-for-broke shots (in his first match he mashed a 4-wood from a fairway bunker), the hitching of his pants, the chit-chat with the gallery, the body English after a booming drive. Fans who were used to watching the icy Hogan systematically win tournaments were in for a treat.

Here’s how Herbert Warren Wind, who covered the ’54 Am for Sports Illustrated, described the 24-year-old:

Palmer is a puzzling golfer to assess. There is no faulting him as a striker of the ball, but his swing is definitely on the flat side, and he compensates for a tendency to come into the ball with a slightly closed face by riding his right-hand grip well on top of the shaft. Throughout the tournament, Palmer would play four or five holes in a row with great authority. Then he would erase the impression that he is almost as finished a shot-maker as Gene Littler was a year ago by smothering a drive or bumbling unsurely with an explosion shot. He is a sound putter and above all a player of tremendous determination.

Palmer cruised to a 5-and-3 win in the fourth round, which set up a blockbuster match with Stranahan, now considered the favorite after Ward and Patton went down earlier in the week. Palmer was just a blip on the national radar, but a win against Stranahan would change that.

It wouldn’t be easy.

Palmer had always struggled against the older and more experienced Stranahan, once losing to him in a 36-hole North and South semifinal, 11 and 10. This time, however, Palmer played one of his best matches of the week, a 3-and-1 win that denied Stranahan the amateur title he coveted most. In the afternoon, Palmer took out reigning Canadian Amateur champion Don Cherry, rallying from 2 down at the turn to reach the semifinals.

Former Yale golf captain Ed Meister was waiting for Palmer the next day, and he pushed the Pennsylvanian to the brink of defeat on the 36th hole. With Meister in with par, Palmer faced a downhill 5-footer to extend the match. It was one of the most important putts of his career.

Palmer calmed his nerves and made it. He closed out Meister on the 39th hole to reach the final against 1937 British Amateur champion Bob Sweeney, a 43-year-old Oxford-educated investment banker from New York.

The two competitors couldn’t have been more different.

“Arnold’s a 24-year-old kid. He had just finished a four-year stint in the Coast Guard, and he’s working as a traveling paint salesman just trying to get through in life,” said Rand Jerris, author, historian and USGA director of communications. “And who does he have in the crowd following him around? His parents. So it’s an incredible contrast in personalities and in playing styles. Sweeney the beautiful swing, the perfect swing. Arnold with the famous Palmer slash, hitting down through the ball aggressively.

“And yet despite these two contrasting personalities and these two contrasting styles, they had a terrific match.”

Sweeney went 3 up after three, but Palmer squared the match after 10 holes. However, by lunchtime Sweeney was 2 up with 18 holes remaining.

Palmer returned for the afternoon 18 with a new mindset – play the course, not the man. It took him until the 32nd hole to pull ahead of Sweeney, but he held on to his slim 1-up lead until the 36th hole, when Sweeney hit an errant drive that was never found. He congratulated Palmer before they reached the green.

“To some extent, a star was born,” said Ian O’Connor, author of the book “Arnie & Jack.” “There was a lot of coverage of that U.S. Amateur, and it was portrayed as the poor kid beating the rich kids at their game. It was almost like Francis Ouimet.”

Palmer still looks back on that week as the turning point in his career.

“The thing that has stuck with me over the years is the fact that I won the National Amateur, and when I won that, that kind of kicked me into gear and put me in the place I wanted to be to spend the rest of my life playing professional golf,” he said. “That’s probably the one thing that I point to now. You can’t ever deny winning the Masters or the [U.S.] Open Championship or the British Open, but the Amateur was something that was a very lofted goal for me, and I spent my early life trying to attain that championship. When I did, it kind of spurred me on to do what I had to do.”

The U.S. Amateur win validated that “frightening” confidence Palmer had when the week started. For the first time he was being asked about his future in golf and the possibility of turning professional.

He also received his first invitation to the Masters.

Palmer tied for 10th in his maiden appearance at Augusta National in 1955. Started in 1934, the Masters was still in its infancy when Palmer arrived, but the beauty of Augusta National had the power even back then to cast a spell over a player when he first drove down Magnolia Lane, and Palmer felt privileged to join Jones’ and Clifford Roberts’ carefully selected invitees.

“I was pulling a trailer … and I parked it on the railroad tracks at Daniel Field and headed for Augusta National Golf Club, and that was one of the great days of my life when I first played the Masters golf tournament,” Palmer said. “I just enjoyed it so much and enjoyed the scene of Augusta and the politics of what made the Masters the Masters.”

In his next two appearances Palmer would finish 21st and tied for seventh, but every year he would learn more about how to play the correct angles and read Alister MacKenzie’s puzzling greens.

Palmer’s confidence grew so much that he felt it was only a matter of time until Jones, Palmer’s boyhood hero and the club’s co-founder, would present him with a green jacket.

By the time Palmer arrived at the 1958 Masters, he had six PGA Tour wins, plenty of money in the bank, and the experience and confidence to win his first major title.

Palmer’s win at the 1958 Masters was clouded by a controversy that would follow him for the rest of his 50 Augusta National appearances.

Starting the final round tied with Snead, Palmer stood on the tee of the par-3 12th with a one-stroke lead over playing partner Ken Venturi. Palmer flew the green with his tee shot and found his ball embedded. Palmer believed he had the right to take relief under a local wet-weather rule, but rules official Arthur Lacey disagreed. Venturi also felt Palmer wasn’t entitled to a free drop. Palmer declared he would play two balls and have the rules committee settle the dispute.

Lacey said that wasn’t allowed either, but a steaming Palmer went ahead and played two balls, taking a double bogey with the embedded ball and a par after taking relief.

Palmer eagled the par-5 13th, and parred 14. While walking down the 15th fairway he received word that the committee had decided he was entitled to relief on the 12th and his par was secure.

Despite a three-putt on 18, Palmer finished at 4 under and had to wait for more than an hour to see if anyone could catch him. The only two men with a chance were Doug Ford and Fred Hawkins, but both missed potentially tying birdies on 18 and Palmer had his first of four Masters titles.

Controversy aside, the 1958 Masters was another turning point in Palmer’s career. No longer was he worried about making it as a professional. He now realized he could challenge Hogan for the title of best player in the world.

It would be a challenge Palmer would happily accept, because Hogan had provided Palmer with a little extra incentive to win his first major.

Palmer had been invited by Dow Finsterwald to play a practice-round match against Hogan and Jackie Burke. On Monday prior to the Masters, Palmer lost a playoff at the Wilmington Azalea Open in North Carolina, then drove through the night and arrived in the early morning hours at Augusta.

Sleep-deprived, Palmer struggled, but Finsterwald carried his groggy partner to victory over Hogan and Burke. In the locker room afterward, Palmer overheard Hogan asking Burke, “Tell me something, Jackie, how the hell did Palmer get an invitation to the Masters?”

A few days later Palmer showed why he was worthy not only of a Masters invite, but a spot among the game’s great players.

Palmer always loved a good challenge.

Hogan’s locker-room snub before the start of the 1958 Masters helped fuel his desire to win his first major, and entering the 1960 Masters Palmer wanted to erase the painful memory from the previous year when he went to the 12th tee in the final round with a one-shot lead, but rinsed his tee shot in Rae’s Creek, made triple bogey and finished third.

He also went into the 1960 Masters knowing he was not only a fan favorite, but he had his own army cheering him on.

Palmer has said the 1959 Masters was the first time he can recall looking up and seeing the words “Arnie’s Army” posted by the soldiers from nearby Fort Gordon who volunteered to work the scoreboards.

Palmer’s fans were treated in 1960 to one of the most thrilling Masters ever. Their hero dropped a 30-footer for birdie on 17, which sent the crowd into a frenzy, and in the excitement Palmer high-stepped across the green to retrieve the ball from the hole.

Needing another birdie on 18 to beat Venturi, who was already in the clubhouse, Palmer smoked a drive down the fairway. His second shot stopped 5 feet from the hole. Palmer backed off his putt when he heard CBS announcer Jim McKay describing the action, then refocused and made the winning birdie.

CBS began broadcasting the Masters in 1956, and Palmer’s birdie-birdie finish made for easily the most exciting Masters of the television era. (It still holds up today.)

“It’s exactly what golf needed: a dramatic presence winning in the most dramatic way at Augusta National,” O’Connor said.

That was just the opening act of Palmer’s historic summer of 1960.

With two green jackets, Palmer turned his attention to winning the next big tournament missing from his resume – the U.S. Open.

Denver’s Cherry Hills Country Club hosted the 1960 edition, and before Palmer arrived, a club member told him the course would suit his game.

The member’s name: President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

But the reigning Masters champion and frequent golf partner of the 34th president didn’t get off to a great start.

The first hole at Cherry Hills played 318 yards in 1960, and with the thin mountain air adding 10-15 yards to every shot, the downhill par 4 was reachable for a player of Palmer’s length.

He had made up his mind to try to drive the green in every round. His opening tee shot, however, found a creek on the right side and he walked off with a double bogey.

From there it was a struggle to stay in the tournament. Palmer opened 72-71 and started the final day eight shots behind leader Mike Souchak. Back in 1960 (and until 1965) the last two rounds were played on Saturday.

Palmer shot another 72 in the third round. Before starting the final round seven shots behind Souchak, he grabbed a hamburger and Coke.

His lunch company included writers Bob Drum from the Pittsburgh Press and Dan Jenkins, then with the Fort Worth Press, and Venturi. Palmer wondered aloud what a final-round 65 would do for his chances to win. After all, a total score of 280 was usually good enough to win the U.S. Open.

“Two-eighty won’t do you one damn bit of good,” Drum declared.

Palmer was so ticked he didn’t even finish his burger. Instead he stormed out to the practice range and blasted drivers until he was called to the first tee.

“The conversation I had with Drum was one that got me on edge and got me ready to go in that afternoon round,” Palmer said. “And, of course, I played some of the best golf I’ve ever played in my life that day.”

His blood pumping from Drum’s remarks, and frustrated by three lackluster rounds, Palmer smoked his drive onto the first green and two-putted for birdie.

The charge was on.

Palmer chipped in for birdie on the second, knocked his approach on the third to a foot, and dropped an 18-footer for birdie on the fourth.

Word of Palmer’s hot start reached Jenkins and Drum, and they ran out to catch up to his group.

“He goes out and birdies the first four holes, so we go running out there to catch up with him at five, walk to the 10th tee, and we’re standing there, and he came over to the ropes and said, ‘Fancy seeing you here. Who’s winning the Open?’” Jenkins said. “Drum said everyone was.”

Palmer birdied six of the first seven holes and made the turn in 5-under 30.

But while Palmer’s charge was sending shock waves around the course, two other players were moving up the leaderboard as well.

Nineteen-year-old amateur Jack Nicklaus was paired in the final round with a 47-year-old Hogan. And the 1959 U.S. Amateur champion from Columbus, Ohio, was holding his own alongside the nine-time major winner.

Just like that, golf’s past, present and future were ready to battle on the back nine at Cherry Hills for the United States Open.

Nicklaus began the second nine with a lead over Palmer, Hogan, Julius Boros, Jack Fleck, Finsterwald, Jerry Barber and Don Cherry.

But the pressure, and perhaps his inexperience, caught up with Nicklaus. He three-putted the 13th and 14th holes, and on 18 Nicklaus missed a 5-footer for par. If he had made it, it would have forced Palmer to par 18 to avoid a playoff.

Hogan, vying for his fifth U.S. Open, stumbled home, too. His third shot at the par-5 17th landed near the pin but spun back off the green and into the water. Hogan removed his shoes, rolled up his pants and splashed his submerged ball onto the green. His shaky putter failed him again, though, and he made bogey.

On 18, Hogan’s drive found the water, and all Palmer had to do was par the 18th hole to win his first U.S. Open title.

After a 1-iron off the tee, Palmer pulled a 4-iron to the left edge of the green about 80 feet from the cup. He studied the thick lie for several moments before taking out a wedge and chipping to about 3 feet.

Palmer settled over the putt, cocked his wrists and popped the ball into the hole. He retrieved his ball from the cup, took off his visor and tossed it into the air.

“It was the best last day ever,” Jenkins said. “It was wonderful to have been there and seen it all. It was such fun because especially when the Open was so great when it was 36 holes on the last day, it was the greatest day in golf, it was a feast. It was several different stories, several different chapters throughout the day, but then it came down to the last 18. Arnold birdies the first four holes and he’s got Jack to contend with, Hogan to contend with and there were so many things that could’ve happened.”

The 1960 U.S. Open is often regarded as the greatest major championship in the history of the game. And if your heart can’t bear to rank it over Nicklaus’ 1986 Masters win or Tiger Woods’ 2008 U.S. Open playoff victory over Rocco Mediate, then the 1960 U.S. Open is the most important major of the modern era.

To win his one and only U.S. Open title, Palmer not only roared from seven shots back in the final round, but he also had to plow through his future rival, Nicklaus, and current rival, Hogan.

And for the second major in a row, Palmer delivered a final-round charge that wowed his army in the gallery, and the fans watching at home.

Having conquered the two biggest events in America, Palmer was now ready to take his one-man revolution overseas.

Back in 1960, the British Open was not the coveted major championship it is today. The cost of traveling to the event, and the measly purse, meant that players often lost money trying to win the claret jug.

If that wasn’t reason enough not to make the grueling trek (and it often was), then this was – players were not exempt into the British Open. That’s right, even though Palmer was the reigning Masters and U.S. Open champion, he still had to endure a 36-hole qualifier just to get into the championship. Even the defending champion didn’t get a free pass. (Fortunately, Palmer would lead the charge to get this silly rule changed.)

Despite those obstacles, Palmer had three very good reasons to fly to St. Andrews in 1960. One was history – 30 years earlier, his hero Bobby Jones had won his third claret jug en route to winning the Grand Slam, and now Palmer had a chance to add his name to the claret jug and equal Hogan’s historic 1953 season by winning the Masters, the U.S. Open and the British Open in the same season. (Unlike Hogan, Palmer would also have a shot at winning the PGA Championship that year since it wasn’t played concurrently with the British Open).

Palmer was also following the advice of his father.

“One of the things – again - that my father taught me when I was a young boy and talking about playing professional golf, he said ‘Just remember one thing, you’ll never be a great player unless you play well internationally,’ so he says ‘put that in your mind and think about it through the years,’” Palmer said. “And I did, and the first opportunity I had to really go to play internationally was the Open at St. Andrews in 1960. I looked forward to that very much and, of course, by some strange act of some very nice people, my father made that trip, too.”

The final reason was business. With television also starting to grow across Europe, Palmer’s agent Mark McCormack saw the opportunity to turn Palmer into a global brand.

“What Mark McCormack realized is when you play abroad you’ve expanded your market, you’re expanding your brand,” said Ron Sirak, writer for Golf World.

But in order for that to happen, Palmer would have to win the British Open and wow the fans and media just like he did in America.

He almost did both on his first attempt.

Palmer finished one stroke behind Kel Nagle at St. Andrews. The Old Course’s infamous Road Hole was Palmer’s undoing as he three-putted it in three straight rounds before making a spectacular up-and-down from the road behind the green in the final round. Palmer added a birdie on 18 to force Nagle to make two closing pars for the win.

While Palmer didn’t walk away with the claret jug, he accomplished a lot in his first trip to the Open. On the flight over, Palmer and Drum kicked around the idea of a new modern Grand Slam, with Palmer ultimately declaring the four events should be the Masters, U.S. Open, British Open and PGA Championship. (Jones’ 1930 Grand Slam consisted of the two Opens, plus the U.S. and British amateurs.)

Palmer also quickly fell in love with links golf. It helped that in the right conditions he could drive several par 4s at the Old Course, and his low, piercing ball flight gave him an advantage when the wind kicked up.

The British fans loved him right back. Everything that made him a hit in the U.S. translated across the pond.

“[Fans] were used to seeing the pros more conservative in their approach to the game, knocking it down the middle and putting it on the green and two-putting,” said Sir Michael Bonallack, former British Amateur champion and R&A secretary.

Palmer was also a big hit with the British media.

“He was a dream come true to the sports writers,” Bonallack said. “They hadn’t seen anything like this on a golf course – his approach to the game, his ferocious swing and [he was] tremendously strong and nothing was impossible. I think he believed he could hit, a bit like Seve in a way, he believed he could do anything. And he could. And of course they always had something to write about.”

Palmer would give them plenty to write about when he returned a year later at Royal Birkdale.

Palmer came into the 1961 British Open with plenty of motivation. Not only was he still miffed about not winning at St. Andrews, he also was hurting after an embarrassing loss at the Masters and a poor showing in defending his U.S. Open title.

He easily qualified, but was in for a rude awakening in the first round. Howling winds nearly canceled the event, and Palmer’s patience was put to the test.

After opening with a 70, Palmer had to call a penalty on himself in the second round when the strong wind caused his ball to move in a bunker at the par-5 16th. He finished with a 73, which was impressive given the conditions.

“The weather conditions in Birkdale were horrendous, and his round of 73 was one of the greatest rounds ever played in bad weather,” Bonallack said. “The weather was so bad that they couldn’t get two rounds in on the Friday, and they had to go into a Saturday, which was very unusual.”

Palmer took a one-shot lead over Wales’ Dai Rees into the Saturday double-header, and this time he wouldn’t fly back to America without his name on the claret jug. Palmer used his low ball fight to fight through the brutal wind and built a four-shot lead by the time he made the turn for the final nine holes.

No surprise, Palmer’s championship came down to a make-or-break shot that dazzled everyone. His tee shot at the par-4 15th came to rest in the right rough. Ignoring the advice of his caddie Tip Anderson, Palmer pulled out a 6-iron, swung as hard he could and watched the ball fly out of the deep rough and onto the green. He left the birdie putt short, but Palmer called it one of the best shots of his career.

Rees finished strong and nearly caught Palmer, but he came up a stroke short. Palmer became the first American to win the claret jug since Hogan in ’53, and now Arnie’s Army had officially gone global.

Perhaps more important, Palmer was starting to change the attitudes of his fellow Americans about playing in the British Open.

“Once the other Americans saw him come here, then they all thought it was something they should try to do,” Bonallack said. “And I think if you win a championship with Arnold’s name on it, you thought you were going to be something special. And so he attracted a lot of the others.”

Palmer’s impact was astounding. Before he won in 1961, Snead and Hogan were the only two Americans to win the Open since the end of World War II. Starting in 1970, just 10 years after Palmer arrived, Americans would win 12 of the next 14 British Opens.

After taking care of his unfinished business at the British Open, Palmer came into the 1962 Masters feeling like he had another score to settle.

At the 1961 Masters, Palmer was walking up the 18th fairway with a one-shot lead and about to become the first player to win back-to-back at Augusta. Palmer even received a congratulatory handshake from his friend George Low. His concentration broken, he made a double bogey and lost to Gary Player by a stroke.

Even worse, as the defending champion, Palmer had to help Player slip into his first green jacket.

The loss cut deep. For the first time, Superman had been knocked down, but in classic Palmer fashion he still had plenty of thrills left for his fans the following year.

Palmer built a two-shot lead heading into the final round, but for the second straight year he nearly gave the green jacket away. After a 39 on the front nine, Palmer was suddenly chasing Player and Finsterwald.

It was time for another charge.

Facing a nearly impossible up-and-down from the right side of the green at the par-3 16th, Palmer holed a 45-foot chip shot to get back into the tournament. He added another birdie at the par-4 17th, and after a par-4 on 18, the Masters had its first three-way playoff.

The 18-hole playoff began on Monday, and it came down to a rematch between Player and Palmer as Finsterwald struggled to a 77.

Palmer once again had to rally on the back nine to catch Player, and he did so in style, firing a 5-under 31 for a 68 and a three-stroke win over Player. It was Palmer’s fifth major championship, and he had now won three of the last five Masters titles. He may not have officially become the King yet, but there was no doubt who ruled at Augusta.

Nineteen sixty-two was shaping up to be a great year for Palmer. After capturing another green jacket, he headed to the U.S. Open, which was being held in his home state of Pennsylvania at Oakmont Country Club, just outside of Pittsburgh.

But his dream of winning a second U.S. Open title vanished when he failed to maintain his lead in the final round, and ultimately lost an 18-hole playoff the next day to the 22-year-old Nicklaus.

Instead of coming into the 1962 British Open at Royal Troon seeking another chance to capture three legs of the modern Grand Slam, Palmer had to shake off another stunning defeat.

He received another proper British welcome from Mother Nature. The combination of bone-chilling wind, rain and a cold putter left a salty Palmer searching for answers. Not to mention he still had to qualify for the British Open even though he was the defending champion.

While the week didn’t get off to an ideal start, by the time it was over Palmer would be reveling in one of the most satisfying wins of his career.

One person Palmer didn’t have to worry about was Nicklaus. The U.S. Open champ opened with an 80 and was never a factor.

Palmer battled an achy back in the first round, shooting 71. His putter came to life the next day for a 69, highlighted by a macho eagle on the par-5 11th where Palmer pulverized a 1-iron and a 2-iron into a stiff breeze and then rolled in a 20-foot putt.

It gave Palmer a huge boost of confidence heading into Friday’s 36-hole finale. He also received a putting tip from wife Winnie to keep his head still. Like any good husband, Palmer listened to his wife. He also proceeded to blow away the field over the final two rounds.

Even the elements gave Palmer a break on Friday. After the tournament started in horrible conditions, warm sunshine greeted the players for the last 36 holes, and Palmer cruised to a six-shot victory to become the first American to defend the claret jug since Walter Hagen in 1929.

Palmer said at the time he had never played a better tournament. In three trips to the British Open, Palmer had won twice and finished second.

Only weeks after the most painful defeat of his career, the now six-time major champion had dusted himself off and reestablished himself as the best player in the game. He also continued to add legions of fans to his army around the world.

“The fans were bypassing the pay gates,” said Angela Howe, director of the British Golf Museum, of the pandemonium Palmer created at Troon. “They were running onto the course, they were racing ahead to get the best viewing position, and as a result of that the R&A had to address how they dealt with the Open and had to introduce crowd control. They were ignoring the stewards, they were bypassing the stewards and they were just so desperate to see this man who had become their golfing hero.”

He was only 32 and at the height of his powers. Surely his name would be added several more times to the claret jug. But unfortunately for Palmer, it would be the last time he would win the British Open, and he would add only one more major to his resume.

Coming into the 1964 Masters, Palmer had won his previous three green jackets by one stroke, two strokes and four strokes (but in an 18-hole playoff). For once he wanted the luxury of having a comfortable lead walking up the 18th fairway.

Given his aggressive style, and thus the potential for a big number, winning by comfortable margins was not exactly a classic Palmer trait. Even over his 62 PGA Tour wins, Palmer rarely won those events by more than two or three strokes. Fifty of his 62 PGA Tour wins were won by three strokes or fewer, and he had a record of 14-10 in playoffs.

Palmer also came into the ’64 Masters in an unfamiliar role but one he relished – underdog. Nicklaus, starting with his stunning win over Palmer at Oakmont in 1962, then became the youngest champion at Augusta when he won the 1963 Masters. Later that summer, he captured his first PGA Championship. Already with three legs of the career Grand Slam at 23, Nicklaus was starting to tug on Superman’s cape.

Palmer was coming off a disappointing year in the majors – for the first time since 1959, he had failed to win one.

But from the start of the 1964 Masters, it was clear this was Palmer’s tournament. With rounds of 69-68-69, he took a five-shot lead into the final round.

Palmer coasted home with 2-under 70, and with a six-shot lead, he finally got to savor the long walk up the 18th fairway. Nicklaus and Dave Marr tied for second as Palmer became the first man to win four Masters titles. The only box left unchecked was beating Hogan’s record score of 274 (Palmer missed it by two strokes).

It was without a doubt his greatest performance at the Masters, and possibly the best tournament he ever played.

Palmer would never win another major, but it was a stunning ascension in the span of 10 years. Palmer had not only won the U.S. Amateur and 42 PGA Tour events (including seven majors), but he elevated the entire sport to a height it still enjoys today. He was the undisputed king of golf.