ROCKLAND, Mass. – Megan Khang’s journey is unlike any other in professional golf.

She’s on a path no one has ever taken to the LPGA, a dreamy yellow brick road that extends beyond the bloody trail her Hmong family navigated on its way out of Laos while fleeing communist death squads during the Vietnam War.

Khang, 20, knows she wouldn’t be playing the LPGA today if it weren’t for her family’s midnight escape across the Mekong River to Thailand in 1975, when they fled the retribution Hmong endured for helping the Americans fight communism in Southeast Asia.

“I know I wouldn’t be here without the sacrifices my family has made,” Megan said. “It’s us against the world. That’s kind of how I look at it.”

This turning to a country club sport so linked with privilege seemed an almost inconceivable ambition for a Hmong family who had little more than the clothes on their backs when they arrived in the United States in 1976.

“It is surreal to me, what Megan is doing,” said Nou, Khang’s mother. “Coming from where we come from, never in my wildest dreams did I imagine something like this.”

That Megan’s father Lee is her coach only adds to the wonderment of the family’s story. He didn’t know what golf was when he arrived in the United States at age 8. He didn’t swing a club for the first time until he was 32.

Now 50, Lee is self-taught, having learned mostly by scouring Golf Digest for instructional articles and watching every YouTube golf video he could find. He has never taken a formal lesson.

When he was 40 and Megan was 10, Lee quit his job as an auto mechanic to become Megan’s full-time coach. With Nou as the family’s primary breadwinner on her elementary school teacher’s salary, they bought a house at Harmon Golf Club in Rockland, Mass., a nine-hole facility Lee says was a “blue-collar” fit for grooming Megan.

“A lot of other golf families thought we were crazy,” Lee said. “I heard what was being said, that it wouldn’t work, that I didn’t know what I was doing, that I was forcing the game on her and I was going to ruin her. They didn’t really know us.”

Megan developed rapidly, qualifying for the 2012 U.S. Women’s Open as a 14-year-old.

She made it through LPGA Q-School and joined the tour as a rookie last year. Today she is the 22nd-highest ranked American in the world, 53rd on the LPGA money list going into the CME Group Tour Championship this week.

It’s just one part of what may be the most amazing backstory in golf, one with more twists and turns and international intrigue than a John Le Carre novel.

There’s even a “forbidden love” angle, the story of how Megan’s parents defied a sacrosanct Hmong tradition by running away to marry.

“What Lee and Nou and Megan have done as a family, it’s an amazing story,” said Xeng Khang, one of Lee’s seven brothers. “I don’t know how they did it.

“We didn’t have any money coming to the United States. We were running for our lives. We left everything behind. Lee and Nou had nothing, and look at them now.”

RICE FIELDS, ROCKETS AND A SECRET CIA BASE

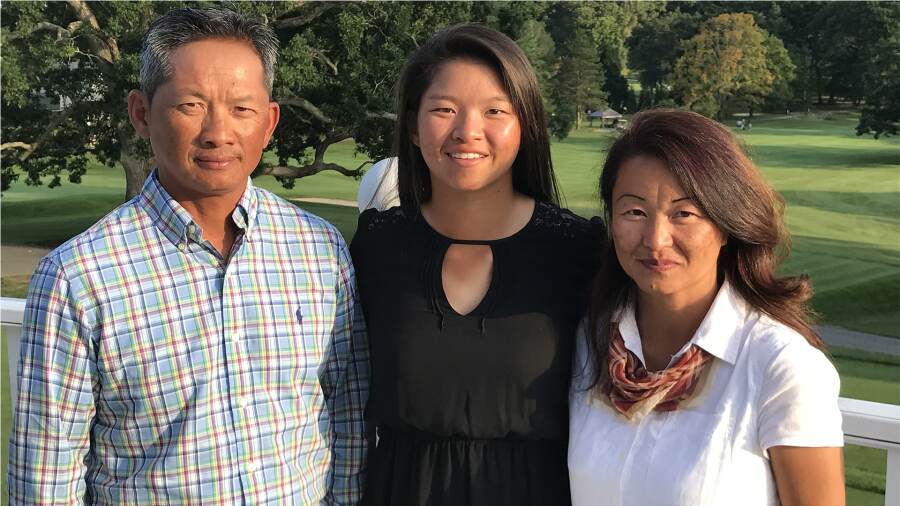

Lee, Megan and Nou Khang (Click here for Khang photo gallery)

Lee Khang nestles up to the railing on the veranda at the back of the elegant Colonial-style clubhouse at Brae Burn Country Club in West Newton, Mass., soaking in the beauty of this historic course 30 miles north of his home in Rockland.

This is where Walter Hagen won the 1919 U.S. Open after legend has it he stayed up all night partying with jazz singer Al Jolson. It’s where Bobby Jones won the 1928 U.S. Amateur.

Megan is inside, mingling with members at a function honoring local players.

Lee’s mind drifts back, to a hardscrabble place that seems more than halfway around the world. He grew up about as far as you can get from country club life. He was born in Long Chieng in the mountains of northern Laos. So was Nou.

A city of 30,000, Long Chieng was wedged in a small valley, with limestone mountains towering like sentinels on every side. It was the largest Hmong settlement in the world, a modest place with mostly tin-shack homes stacked tightly together. Most homes didn’t have indoor plumbing, but many had fortified bunkers in their backyards, for those nights when rockets fell like rain.

A 4,200-foot runway stretched through the middle of the city, giving this tribal community one of the busiest airports in the world, with military transports and bombing missions moving through like rush-hour traffic.

Long Chieng was the CIA base for the American “secret war” in Laos in the ’60s and ’70s. It was a “secret war” because the Geneva Accords established a neutral Laos, and because the American people didn’t know the CIA was conducting covert operations there for 15 years.

The CIA trained Hmong as soldiers and pilots to fight the communists during the Vietnam War.

Lee was one of 12 children in a family of rice farmers. In 1975, when Laos began to fall, he was 7. At least, he thinks he was.

“We didn’t have birth certificates,” Lee said. “We didn’t celebrate birthdays. We didn’t really know our birthdates. I was born in the growing season in 1967.”

Lee remembers little of the family’s life in Laos, almost nothing of the exodus.

“I remember the gun shots,” Lee said. “I remember holding on to a boat for dear life when we left Laos. That’s about it.”

Xeng Khang, one of Lee’s brothers, who now lives in Kissimmee, Fla., remembers the family’s home rumbling violently with the crack of enemy cannon fire in an attack on the airport. He remembers his parents frantically herding everyone into the backyard to hide amid the giant banana trees, because they were sure the communist guerillas were finally going to come barreling through their front door.

“The trees shook for two hours with the rockets exploding,” Xeng said.

Xang “Sam” Xiong, who would become Megan’s uncle after marrying Nou’s sister, Ly, remembers racing out of his family’s house amid that siege and bolting into the jungle.

“We were going up over a hill, above the city, and you could hear the missiles going right over the top of our heads,” Sam said. “We were ducking. That’s how close they seemed.”

Sam’s aunt, his father’s sister, was killed that night when a rocket landed next to her home and shrapnel blew through the walls.

“They said she was clinging to her daughter, who wasn’t hurt,” Sam said. “It was so sad.”

The next day, with the big guns silenced, Hmong families slowly made their way back home. There they saw casualties littering the runway.

“We didn’t get too close, but you could see the bodies lying out there,” Xeng said. “There were four or five enemy soldiers.”

Xeng said that’s the day the family packed up and left Long Chieng, to make their way to Vientiane, the capital city of Laos.

Vientiane was built on the banks of the Mekong River, the rolling brown monster of water that separated Hmong from safe haven and sanctuary in Thailand.

A HAZARD LIKE NO OTHER ...

The Mekong River, across from the Luang Prabang golf course (Getty Images)

Jane Hamilton-Merritt, a scholar of Southeast Asian studies and a former war correspondent, remembers standing on the Thai side of the Mekong River in the late ’70s, watching one dead body after another float past her, gruesome evidence of a massacre up river.

The Mekong River, she said, was Asia’s version of the Berlin Wall, separating the Hmong from Thailand. Though there were no bridges connecting Laos and Thailand, many Hmong attempted the dangerous crossing.

“It was a torturous decision to leave Laos, for Hmong to say `I have given up, I will be resettled,’” said Hamilton-Merritt, who wrote the book “Tragic Mountains,” which documented the Hmong’s role in the war.

Xeng Khang was about 15 when he sneaked his parents out the back door of a farmhouse outside Vientiane after a communist patrol arrived.

Nautou, Xia Ge and Yong Yang, the oldest Khang brothers, were arranging for a friend in Thailand to bring a fishing boat to take the entire family across the Mekong River.

“But it was too dangerous to go during the day,” Xeng said. “We had to go at night.”

Lee was huddled between his brothers in the back when their truck was stopped at a checkpoint. “The guards wouldn’t let us pass,” Xeng said. “But one of my brothers pulled one of the guards aside and stuck a wad of money in his pocket, and they let us through.”

The fishing boat was built to carry only about six people, but 12 Khangs boarded it. They made their way undetected to Thailand and an eventual series of refugee camps.

At the second camp, Ban Vinai, the Khangs were among a legion of families assigned to tents. “In a lot of ways, it was like a prison,” said Sam Xiong, who also stayed at Ban Vinai. “There was a barbed-wire fence surrounding the entire camp. You couldn’t leave.”

Hmong families waited for months for sponsors to finance their resettlement in Australia, France, Germany, Argentina, Canada or the United States.

After six months at Ban Vinai, the Khangs learned that a private American party had agreed to sponsor their resettlement, but there was only enough to finance four of their family.

In April 1976, Lee left for the United States with his oldest brother, Nautou, Nautou’s wife and young son.

Lee was 8. The rest of the Khangs made it over in two other waves of sponsorships, with all of them reuniting within a year in Brookline, Mass.

All 12 of the Khangs shared a sponsored home, a three-story house near the Boston College campus. It was a good neighborhood.

Lee slept on a mattress in a hallway, and he couldn’t have been happier about it.

“There were three in a bed in some rooms,” Lee said.

None of the Khangs spoke English when they set foot on American soil, but Lee learned it in a hurry when he was ushered off to elementary school.

“You learn things more quickly when you’re trying to survive, when you’re in an uncomfortable environment,” Lee said.

Brookline was wealthy, and the contrast with Long Chien couldn’t have been more severe.

The Country Club, one of the oldest golf clubs in the United States, home to Francis Ouimet’s historic U.S. Open upset in 1913, was just two miles south of Lee’s new home.

Lee said he had “a bunch of rich kids as friends.” His impoverishment – the whole family was on welfare – didn’t seem to matter to them, but it did to him.

“I almost didn’t want to go to the grocery store with my parents, because my mom and dad didn’t speak English,” Lee said. “But I had to help them count out the food stamps.”

Lee would cringe when they reached the register to check out, when he had to start peeling out food stamps to pay. It was awkward when friends would be in the store.

“It was embarrassing,” Lee said.

Julian Millan, Lee’s best friend in the neighborhood, saw how this affected Lee.

“He tried harder than everyone else at everything, and he was better than most of us at everything,” Millan said.

Lee started making his own money when he was 10, shoveling snow and cutting grass. He got a job stocking shelves in a small pharmacy when he was 11. He remembers working a lot after school, making pizzas for a while, taking tickets at a movie theater and pumping gas.

Lee’s brother Yong Yang enrolled at a technical college and became certified as a mechanic. Eight years after landing in the United States, the brothers pooled their money and bought a Mobil gas station. They made enough there to buy a Texaco station.

“I pumped gas for them and fixed flat tires,” Lee said.

And they taught him all about car engines. When the brothers sold the gas stations to buy an auto repair shop, they made Lee a partner at Brothers Auto in Providence.

That’s where the family would face its next great threat.

It’s where Lee met Nou.

DISOWNED AND SHUNNED BECAUSE OF FORBIDDEN LOVE ...

Nou and Lee Khang (Khang family)

In the Hmong culture, clan members are like brothers and sisters. They’re forbidden from marrying members of the same clan, even if they aren’t actually blood relatives.

A Khang could not marry a Kue. Couldn’t even date one.

So when Lee told his younger brother Yer that he was going to go ask that pretty girl on the other side of the room to dance during a Hmong New Year’s party in Providence, R.I., Yer tried to stop him.

“No, no, no, no, no,” Yer said. “She’s a Kue. We’re from the same clan. You cannot dance with her.”

Lee smirked.

“Oh yeah, watch me,” he said.

Lee sauntered over, only to be turned down by Nou.

“I knew he was a Khang, and I knew I wasn’t supposed to dance with him,” said Nou, whose family had also escaped Laos in the 1970s. “But he kept saying, ‘It’s no big deal,’ and he wouldn’t give up, so I danced with him.”

Lee was 19, Nou was 16.

The romance didn’t take flight until a couple years later, when they began seeing each other regularly in Hmong circles in Providence, where Lee was working and Nou was living. They began dating seriously. Actually, it was more like sneaking around, so family wouldn’t find out.

But the family did find out.

Lee’s mother heard about it and told Nou’s mother.

“All hell broke loose after that,” Lee said.

Nou was 20 by this time, in college, and Lee was 23, working as a mechanic.

After word reached Nou’s mother, there was a showdown.

“It’s wrong,” said Tru, Nou’s mother. “It’s a disgrace. Wait until your father gets home.”

Nou panicked. She grabbed her purse and raced out the door. She ran away, hiding in a hotel room.

Lee found her, but it took awhile for Nou to get up the nerve to return home.

When Nou did, it seemed as if the whole Kue clan in Providence was waiting for her - brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles and cousins.

“My father was a community leader, and they told us we were making him lose face,” Nou said.

Nou was swept upstairs with the women, and Lee was surrounded downstairs by the men.

Nou’s father, Xay Ge, was a former drill sergeant. “He told me if we were back in Laos, he would kill me,” Lee said. “He said I’d be 6 feet under.”

With his long hair and leather jacket, Lee was altogether too Americanized for Nou’s father. Yet the younger man was undeterred.

“There are some good Hmong customs, and there are some dumb ones,” Lee said. “This was about love. I knew in my heart we weren’t wrong. We weren’t related by blood.

“We told them we were going to get married, even if they didn’t approve. They said, in that case, we disown you.”

Lee’s parents were equally outraged.

“I don’t want you carrying my name anymore,” Lee’s father said. “Find a new name.”

Hmong custom requires a man to negotiate the price of a dowry to pay his bride’s family. The maximum amount allowed by Hmong rule at the time was $5,000. Rather than negotiate, Lee sold his Toyota Supra, marched into Nou’s house, peeled off $5,000 in cash and slapped it on the table in front of Nou’s father.

It took more than a year, but both sets of parents eventually softened.

“They saw how we were making a good life together,” Nou said. “Lee had his own business with his brothers, and I was beginning to teach.”

When Nou became pregnant with Megan, it closed the gap with the parents.

“They welcomed us back,” Nou said.

Nou’s father held a reunion ceremony. As part of a Hmong custom, he tied a string to Nou’s fingers, a blessing that signified a new beginning.

“It meant so much to me,” Nou said.

LIKE FATHER, LIKE DAUGHTER ...

Megan splits the first fairway with her tee shot in a practice round at Harmon Golf Club, her home course in Rockland. Mom’s at the wheel of the golf cart, Dad’s on the range giving a lesson to a local junior.

“Dad’s a kid at heart, and we’ve had a lot of fun playing matches here,” Megan said. “Our smack talk is pretty good. Mom says she raised two children.”

Nou didn’t really like the house they bought on the course, but Lee sold her on the nine-hole neighborhood facility as being the perfect place to groom Megan. It has a muni feel with a challenging layout and a good practice facility, all at a price the family could afford.

“It used to be a pig farm,” Lee said.

This wonderful golf journey the Khang family is making together may not be filled with the life-and-death challenges of Lee’s and Nou’s youth, but there are challenges nonetheless.

Lee has been Megan’s swing coach, caddie and mental coach for a long time now, but it’s no easy trick balancing all of that with being a father.

How do you go from pushing your player as a coach, to being under your player’s rule as a caddie? How do you blend being a father with all of that?

It complicates family dynamics.

After a rough day on the course not so long ago, Lee stunned his daughter.

“I turned to her and said, ‘I hate you,’” Lee said. “She looked at me shocked, and then I said, ‘I hate you because you’re exactly like me.’ I told her we are both stubborn, and I wished she was more like her mom.”

They laughed.

“My dad makes the game fun,” Megan said. “He is crazy in love with golf, and he passed that on to me. We have great times together, but we bump heads, too.”

Lee has been Megan’s caddie most of her two years playing the LPGA, but they’ve taken breaks from each other. They’re on a break now. Megan played the entire Asian swing with a new caddie, with Lee back in Massachusetts the whole time. She finished a career-best, T-3 last week at the Blue Bay event in China and is now inside the top 100 in the Rolex Rankings, at 96th.

“It’s Megan’s life, and she needs space to grow,” Nou said. “She needs to start making her own decisions.”

Megan says her mom is the glue that holds the golf and family pieces together.

“She never lets us forget that family is more important than golf,” Megan said. “When Dad and I have disagreements, she has a way of getting us to see each other’s perspectives.”

At 20 now, Megan is beginning to stretch her wings, to venture farther from the nest.

“I like having another caddie sometimes so my dad can just be my dad,” Megan said. “But it’s hard, because nobody knows my game like he does, nobody can help me the way he does.”

Lee agrees Megan needs space to grow up, but the coach and father in him will never stop wanting to help. That’s the challenge he faces now, as he tries to lighten his grip on the reins while still helping Megan improve.

Lee wonders sometimes if he sheltered Megan too much from the hardships he and his wife endured growing up in Laos and then on welfare in the United States.

He wonders if sharing more of the desperation he and Nou felt in their childhood would have given Megan an even greater edge today.

“I didn’t want Megan to feel the pain and suffering we felt, where we didn’t always know where our next meal was coming from,” Lee said. “I protected her from all of that, and I shouldn’t have.

“Megan has amazing talent, and she’s so kindhearted, but she’s still young and doesn’t understand how the real world works, or the real disadvantages we faced. Maybe knowing would have helped her play with a chip on her shoulder, maybe play with even more passion.”

Nou hears that knowing Lee is shaped by the wanting of his youth, as well as the ambition and resourcefulness all that wanting created.

“Lee doesn’t sleep much,” Nou said. “He is always thinking about ways he can help Megan, ways to help her with her swing. His mind is always working.”

Lee said he had a heart-to-heart conversation with Megan before she left for Asia without him.

“Things happen,” Lee said. “But I told her I hope she understands that my love is unconditional for her, that I will take a bullet for her, no matter how angry she might be with me or I might be with her.”

That sounds like the same emotional compass the Khangs and Kues used to make their way out of the jungles of Laos and to find their way conquering all those obstacles lined up against them as refugees in a brave new world.