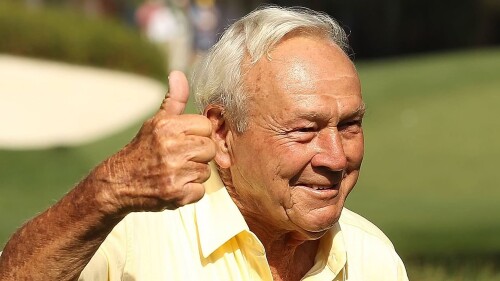

Arnold Palmer had been particularly uneasy about this night’s speech. He’d made hundreds of speeches before, and was never one to disappoint, but this night was different.

He didn’t have a script, but then again, he never did. He once addressed a joint session of Congress, and before he was called to the floor of the House, aides asked for the written script. There wasn’t one.

There were no politicians, dignitaries or celebrities in the room this night. No, this room was filled with people important to Palmer not for the characters they played in the public eye, but for the character they portrayed in everyday life.

It was his 50-year high school reunion, where former classmates and teammates gathered at Latrobe Country Club in Latrobe, Pa., to reminisce, swap stories and catch up with the man they knew as a boy. The man, who, despite all his worldwide fame and fortune, was still just Arnie Palmer to them. They didn’t share the same bloodline, but these people were family.

When the time came for Palmer to speak – just like so many times before – he knew exactly what to say:

“We’ve all gone a lot of places since our days growing up here in Latrobe. And if there’s one thing I’ve learned in all those years, it’s this: Your hometown is not where you’re from. It’s who you are.”

Click on the title or the image below the title to read all GolfChannel.com “Arnie” articles.

Arnold Palmer was born on September 10, 1929 – the first child of Deacon and Doris Palmer in Latrobe, a small steel town 30 miles southeast of Pittsburgh.

The Palmers lived in a modest house near the fifth hole of Latrobe Country Club, where Deacon was the club pro and greenskeeper. Arnold’s mother kept the pro-shop books and oversaw the family finances. When Arnold was 2, his sister Lois Jean (later nicknamed Cheech) was born.

Arnold and his sister were born just as the Great Depression’s effects were taking hold on America. Cheech recalls only two rooms in their house having heat – the kitchen and living room, thanks to a fireplace. While not affluent, the Palmers made enough to get by.

“We always had enough to eat,” Cheech said, “but I can still hear Daddy saying, ‘By God if you put that on your plate you’d better eat it.’”

Fortunately, Arnold’s childhood isn’t characterized by what was in the Palmer bank account, but by the richness of love he received from his family and the town.

“Arnold had a great childhood, almost an American idol of childhood,” said James Dodson, co-author of Palmer’s autobiography, “A Golfer’s Life.” “He grew up with the free run of the golf course and the creeks around Latrobe, and he was an athletic kid. He played a lot of different sports. … He loved being outdoors; he never wanted to be indoors. He was in creeks and always in the middle. He was a scrapper – a lot of fist fights.”

In his autobiography, Palmer shared two of his earliest memories.

The first: When he was 3 years old and carrying a fresh quart of milk up his grandmother’s three front steps, he tripped and fell on the milk bottle, shattering the glass and slicing nearly the entire side of his left hand.

“I suspect I may have cried,” Palmer later recalled, “though perhaps not. It certainly wouldn’t surprise me if I didn’t, because even then I knew my father and my grandfather were tough and seemingly unsentimental men, and I instinctively knew I wanted to be like them.”

The second memory: “When I was 3 … my father put my hands in his and placed them around the shaft of a cut-down women’s golf club. He showed me the classic overlay, or Vardon, grip – the proper grip for a good golf swing, he said – and told me to hit the golf ball.”

“Hit it hard, boy,” Deacon said. “Go find it and hit it hard again.”

While he excelled at golf, Palmer was indifferent in school.

“Admittedly, I wasn’t the best student in high school,” he said. “I made decent marks in math because it had a useful purpose on the golf course (keeping score and tallying up bets), and pretty ordinary ones in English and history.”

Deacon was the head pro at Latrobe County Club, but back in the 1930s, club pros were not particularly respected by the membership they served. The Palmers weren’t allowed to play the course except early mornings before members arrived or late evenings after they’d left. Despite the restrictions, Arnie squeezed golf in whenever he could.

When he wasn’t with his dad or his dad’s work crew, he was sometimes permitted to hack a ball around in the rough. Occasionally, when nobody was looking, he’d sneak onto the putting green for a few moments of practice.

Before he turned 8, Palmer broke 100 for 18 holes and could hit the ball more than 150 yards – a feat that turned out to pay dividends.

“On summer days, I’d hang around the ladies’ tee near the sixth hole waiting for Mrs. Fritz to come along. An irrigation ditch crossed the fairway about 100 yards out, and Mrs. Fritz could never quite carry it. ‘Arnie,’ she’d call over to me sweetly, ‘come here and I’ll give you a nickel to hit my ball over that ditch.’”

He never once failed.

The swimming pool, dining room, locker room and club lounge at Latrobe CC were also off limits to the Palmers.

“I was raised in a country-club atmosphere, but I was never able to touch it,” Arnold said. “It was like looking at a piece of cake and knowing how good it was, but not being able to take a bite.”

Because Arnie and Cheech were forbidden to swim at the club, they frolicked in a rock-edged stream that skirted the golf course and their house near the old sixth hole.

“Ironically, that creek was the source of the pool’s water, and our favorite running joke for years was that we at least got to pee in the club’s swimming pool water before the country club kids did,” Palmer said.

On Friday nights, Deacon and Doris would take their kids to the movies. Afterward, Deacon hosted a big poker game at the Palmer house, and on Saturday nights, Doris often prepared a feast and invited couples to come over and play cards.

By age 11, Palmer was caddying at the club, which meant he got to play with other caddies when the course was closed on Mondays. His game improved rapidly, and he won the club’s caddie tournament five times.

Latrobe CC had small, moist greens that best received a low, hard shot, and Palmer groomed his game around hitting low liners that would land and roll rather than high shots that would land softly. He became adept at hitting a 1-iron and could get 210 to 230 yards out of it. Latrobe CC had very few bunkers, and Arnold’s father wouldn’t allow him to chip and scuff around the greens. As a result, Arnold’s short game was his weak link for years.

A dozen years after Arnold was born, Deacon and Doris felt financially secure enough to have more children. Arnold’s brother Jerry was born in 1944, his sister Sandy in 1948.

Beginning at age 12, Palmer began playing junior tournaments around Pennsylvania. He shot 71 to win his first-ever high school match. He won the West Penn Junior, five West Penn Amateur titles, the Pennsylvania State High School Championship twice and then enrolled at Wake Forest on a golf scholarship.

He regards his years at Wake Forest as some of the happiest of his life.

“Out from under my father’s stern sphere of influence for the very first time, I spread my wings and had a hell of a lot of fun, forged a host of lifelong friendships and got my first taste of winning golf tournaments on a national level,” Palmer said. He was a two-time winner of the Southern Conference Championship and two-time National Intercollegiate medalist.

But his Wake Forest years were also marked by tragedy. His best friend, Buddy Worsham, whom he had followed to Wake Forest, was killed in a car accident in 1950.

Palmer was shaken to the core and his grades rapidly declined. He dropped out of Wake Forest and enlisted in the Coast Guard. After three years of service, he received an honorable discharge and was readmitted to Wake Forest, but left again, without graduating, after one semester.

Not knowing what he wanted to do with his life, he returned to Cleveland, where he had been stationed in the Coast Guard, and took a job as a paint salesman.

Wanting to remain in golf yet not wanting to become a club pro like his father, Palmer was torn.

“Back then, the golf pro wasn’t even admitted to his own clubhouse,” he said. “And I was too proud to live my life as some kind of second-class citizen.”

Luckily, decisions about his future became much more clear after he won the 1954 U.S. Amateur, then turned pro shortly thereafter.

Professional golf took Palmer to all corners of the earth, but he always returned to Latrobe. There, he has always been, and always will be, Arnie Palmer.