He was the son of a head pro who doubled as a greenskeeper. So maybe it’s no surprise that when there was something to be done – or somewhere to go – Arnold Palmer figured out how to go about it himself.

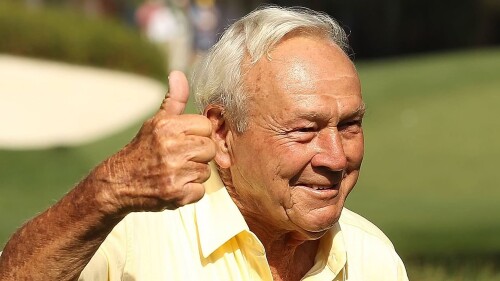

Beyond being the man who helped introduce golf to the masses, beyond his role as a philanthropist, an entrepreneur, a champion and an all-around celebrity, Arnold Palmer was – to borrow a now-hackneyed term in the American lexicon – something of a maverick.

And, really, he could have subbed for Tom Cruise in “Top Gun.” After all, Palmer can actually fly.

“He would have made a great fighter pilot,” says longtime Palmer co-pilot Pete Luster. “You can just tell flying with people – some folks get over 30 degrees of bank and get uncomfortable.

“Not Arnold Palmer.”

Though he never did tangle with the Red Baron, the moment that sparked Palmer’s career as an aviator was not without drama.

Click on the title or the image below the title to read all GolfChannel.com “Arnie” articles.

Traveling to an amateur event aboard a DC-3 fixed-wing at the age of 20, Palmer, in the middle of a thunderstorm, found a far more forceful motivation when his plane was struck by lightning.

“I was sitting on the left side of the airplane – I can remember it as if it was yesterday – when suddenly this ball of fire started rolling around in the aisle,” Palmer recounted in an interview with FlyingMag.com in 2011. “I had no idea what it was, but it scared me.

“That’s when I really knew that if I was going to continue to fly, I needed to know what was happening in the airplane.”

St. Elmo’s fire – the electrical phenomenon Palmer witnessed – is named after Saint Erasmus of Formia, the patron saint of sailors, who themselves disagreed over the meaning of such an event. On the one hand, electricity in the air is bad news for anyone surrounded by water aboard a large open-air ship. On the other hand, some sailors saw it as a positive omen, signifying the presence of their patron saint.

In this case, out of the water and in the air above, it launched a 55-year career in the cockpit.

Roughly six years later, in 1956, after finishing his rookie year on the PGA Tour and winning his first event, the 1955 Canadian Open, Palmer had set aside enough money to begin flying lessons.

In1961, he bought his first plane, an Aero Commander 500. By ’63, he had already traded up to the 560F. And not long after, he was in charge of his own Learjet.

He also had a handful of other reasons – separate from St. Elmo – to take to the skies.

First, there was family.

Says Palmer: “I could fly to exhibition matches and to tournaments and I could be home at night. I realized that my life on the golf course was going to be something that I could do and still have time with my family.”

Second, there was the escape.

Says Cori Britt, vice president, Arnold Palmer Enterprises: “Flying was therapeutic for him, because flying requires total concentration. When he got out of a golf tournament, he couldn’t be thinking about what would happen on the golf course. He got in there, that was a bit of his therapy; he unwound.”

And third, there was his personality.

Says Palmer biographer Thomas Hauser: “Arnold was not one to stand in line and wait at gates to get on an airplane if he could avoid it.”

And from that desire to get wherever he had to without waiting, Palmer went somewhere faster than anyone else ever had.

Out of the 20,000 hours Palmer spent flying, 57 of them, in addition to 25 minutes and 42 seconds, would go down in history. Taking off from Denver, and making stops in Boston, Paris, Tehran, Sri Lanka, Jakarta, Manila, Wake Island and Honolulu, Palmer set the record for the fastest circumnavigation of the globe, a record that still stands today. His time would have been even faster had he not stopped to ride an elephant in Sri Lanka and meet with the president of Manila.

As much as he loved flying, and no doubt still cherishes his record, Palmer’s initial motivation for the trip was a little less noble.

Says Palmer: “That came sort of as a result of a deal that I made with Harry Combs who was the president of the Learjet company. He said if I flew a Lear 36 around the world that he would make a deal with me on a new Lear 35. Well, that was enough for me. I got into the Lear 36 and flew it around the world and set a world record, a couple records actually.”

As for that new Lear 35?

“Harry Combs backed out of my deal,” Palmer said. “That was the end of that.”

Instead, Palmer ended up with one Cessna Citation model after another, all the way up to his final flight on Jan. 31, 2011. Unlike his decision to gradually step away from professional golf, this was a choice with a firm deadline. Palmer’s license was set to expire, and rather than re-up for a new one at age 81, he staged his last flight from Palm Springs, Calif., to Orlando, Fla., announcing on the tarmac upon arrival that he was retired.

Now 85, he’s still flying – he’s just back in the cabin rather than the cockpit. And he’s not always happy about it. Asked whether it was harder to give up professional golf or his other great love, Palmer answers:

“Flying was tough, because I can still play golf. I can’t play as well as I’d like to, but I still get out on the golf course and play. Flying – I sit in the back and read the paper or read a book. That’s tough, that is something that is very frustrating.”

“He loved the gadgetry of it,” adds Hauser, summing up both the new-found frustration and the long-standing necessity of flight in Palmer’s life. “It also was a way to move his career along, particularly when he had all the business ventures in addition to playing golf. It really became essential to his businesses and his way of life.”

Speaking of those business ventures, it’s worth pointing out that Palmer had approximately 300 other reasons to fly around the world – his golf courses.

Now based out of his own Bay Hill Club & Lodge, the Arnold Palmer Design Company, in its 42-year history, is responsible for tracks in 37 states and 25 countries. The firm prides itself on doing everything from renovations to remodels to original designs.

But Palmer’s roots as a world-renowned course designer date back to far more humble beginnings than a 2006 decision to move Pebble Beach’s sixth fairway closer to the Pacific Ocean. No, this story starts nearer the Atlantic Ocean, in Winston-Salem, N.C.

While a member of the golf team at Wake Forest, Palmer and his teammates built their own practice facility. (Worth noting, the Demon Deacons have since upgraded to the posh Arnold Palmer Golf Complex, just a small step above what Arnie and the boys once carved out themselves.)

Already known for his amateur golf accomplishments after leaving Wake Forest, Palmer was asked during a three-year stint in the United States Coast Guard to embark on his first original design in Cape May, N.J. As told on the design company’s website, “With a rake, shovel and hand-push mower, Arnold was directed to a weed-choked grassy patch of ground between the base’s air runways.”

“That probably was not the most challenging layout but certainly was the most exhausting to create,” says Palmer. “When I was done, it was a pretty rudimentary layout – a nine-hole chip and putt, really – but I was pleased with my efforts, and the officers who played it were delighted to have a place to hit balls.”

More than a decade later, Palmer would help his father expand Latrobe Country Club from a nine-hole course into an 18-hole championship layout.

And more than four decades into his design career, Palmer’s theory on golf course architecture draws its roots from those grateful Coast Guard officers playing beside runways in Cape May.

“He’s constantly reminding us and doing his part to let us know, ‘Hey, it’s all about fun,’” says senior course architect and vice president of Palmer Design Thad Layton. “Our job is to make golf courses primarily fun, because if you’ve failed on that level, it didn’t really matter what else you did.”

Layton, along with fellow architect and co-vice president Brandon Johnson, is helping to carry on the Palmer brand. While Palmer himself still has plenty of input in the design of his ongoing projects – two in China and one in South America – he’s also placed his faith in Layton and Johnson to execute his visions. Although by no means retired from the design firm, here, too, Palmer is beginning, after 42 years in the design business, to move from the cockpit back to the cabin.

Layton, in particular, has come a long way with Palmer. He started as an intern in 1997 while still a student at Mississippi State and is now one of the three heads of the company along with Johnson and Palmer. Layton remembers his first interaction with the boss.

“He is just someone who is really approachable,” Layton says. “Being a boy from Mississippi, there’s not a whole lot of celebrities running around there … but he just struck me as a very down-to-earth guy, very humble.”

Fourteen years after officially joining Palmer Design in 2000, Layton has traveled the world with Palmer on project after project. That small-town kid from Mississippi eventually called Palmer not only his design partner, but his pilot.

A pilot with a unique talent for sticking the landing. Just ask anyone who’s ever flown with him.

“That was one of his fortes,” says Luster, the co-pilot, “because when it came time to land, that was when he really perked up. Kind of like hitting that first drive off No. 1 in a tournament. He always rose to the occasion.”

Don’t believe the guy who sat with Palmer in the cockpit? How about hearing it from somebody in back?

“The last time I got to fly with him, when he was still piloting, was a flight from Orlando to Palm Springs,” remembers Layton. “That was the smoothest landing I’ve ever experienced. I didn’t even know we were on the ground.

“Also how fast it was. It typically takes seven hours and a connection to get from Orlando to Palm Springs and we were there in four hours flat. On the way back, it was about three and hours and 10 minutes thanks to a tailwind. He did the whole the thing round trip in less time than it takes for a one-way flight.

“It was … it was pretty cool.”