Greatness gains nothing by comparison shopping. But an examination of Tiger Woods’ career isn’t complete without acknowledging a story arc with distinct offshoots.

The 1997 Masters was historic, both culturally and competitively. The ’00 U.S. Open was unbridled dominance, while the ’08 U.S. Open was the power of pure will. The ’19 Masters was nothing short of redemptive.

Each holds a place in Woods’ competitive lineage, and each offers a window into a career that can be neatly categorized into three eras - two of which would qualify as first-ballot Hall of Fame resumes on their own (and an argument can be made that the “other” years could also qualify for a locker in St. Augustine, Florida).

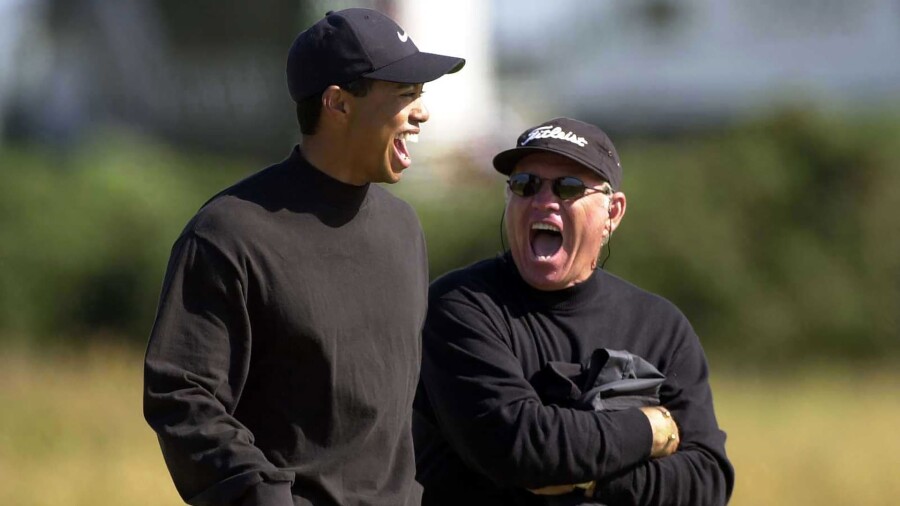

The Butch Harmon era began well before 1996 but, for scorecard purposes, started when Woods won twice on the PGA Tour shortly after turning pro. Woods was already a singular talent with untold potential, but his 12-stroke victory the next year at Augusta National set a lofty tone for the Harmon years.

Harmon and Woods split at the end of 2002, but not before Tiger won eight of his 24 major starts, 34 official Tour events (for a 27% success rate) and was named the Tour Player of the Year five times.

The accolades will flood Wednesday’s induction ceremony into the World Golf Hall of Fame. But for the Harmon years, it’s the “Tiger Slam,” with victories at four consecutive majors starting at the ’00 U.S. Open, that defines the era. Or maybe it’s a run that included seven major victories in 11 starts, from the ’99 PGA Championship to the ’02 U.S. Open, that paints the perfect picture.

For Woods, greatness defined – even just a slice of greatness during the Harmon years – is a moving target with almost endless options. Pick your accolade and it serves a purpose.

But it’s not the Grand Slam victories nor the grand total of triumphs that stand out for Harmon, who at 78 has gone into semi-retirement but remains plenty active from his studio in Las Vegas. For the legendary swing coach, Tiger’s greatness was, at least in part, defined by consistency.

“It’s the 142 cuts in a row, that was special,” Harmon said recently. “He never was complacent his entire career and that stretch was the best example of that.”

That streak, which is the longest on Tour by 29 cuts, began at the ’99 Buick Invitational and lasted through the ’05 Byron Nelson. During Woods’ tenure with Harmon, he missed just a single cut (’97 Canadian Open).

Harmon concedes that the 20-something version of Woods was curious and never content. Even after winning the ’97 Masters by a dozen strokes, his training and practice intensity only grew. He didn’t just want to win, he wanted to dominate.

“He went out Sunday at the 2000 U.S. Open [with a 10-shot lead] and he didn’t want to make a bogey. He didn’t want to just beat you, he wanted to beat you by five, by 10, by 15,” Harmon said.

Comparing eras, specifically Harmon’s years versus Woods’ time with Hank Haney, is the fodder of sports radio nonsense, but there is room for an examination of how Woods evolved as a player with different influences in his game.

With Harmon, Woods was a driving machine; the Haney years were defined by some of the best iron play the game has ever seen. Part of that distinction was dictated by the style of play in each decade.

Before the introduction of larger clubheads and more forgiving, less-spinning golf balls, accuracy off the tee mattered and when Woods first arrived on Tour he was among the best. Under Harmon, Woods led the Tour in total driving twice (1999 and ’00). At his most dominant, the 2000 U.S. Open, he dismantled the field, hitting 41 of 56 fairways. During the Haney years (2004-10), his total-driving average rank was 51st and his focus turned toward distance as the game evolved.

“He worked to bring his trajectory down during those [early] years and backed off on length and became more conservative,” Harmon said. “At that time, hitting more fairways was important and he was good at that.”

During those halcyon years, Harmon described a work ethic that bordered on the obsessive. Even after dominant performances at Augusta National and Pebble Beach, there was always a workmanlike drive to improve. That desire didn’t change as he aged, but his ability to put in the time did.

Harmon’s version of Woods was largely untouched by the injuries that made his years with Haney and beyond such a challenge. Other than a 2002 procedure to have a cyst removed and fluid drained from his left knee, there were none of the surgeries, strains and serious injuries that would become the norm.

Yet for all of Woods’ physical gifts and his relative health during his years with Harmon, it might have been the hunger of youth that fundamentally separated the eras. Early in his career there was a curiosity that understandably diminished in his later years, the way it does for many.

It was just before the ’97 Masters and Harmon recalled talking with Woods about the course and its history.

“He was enamored with all the old-time players and I was telling him my dad’s greatest feeling when he won at Augusta was he had a five-shot lead [coming down the stretch], he felt like he couldn’t lose,” recalled Harmon, whose father, Claude, won the ’48 Masters by five shots. “I told Tiger, ‘That’s going to happen to you.’”

At the ’97 Masters, Harmon remembered that conversation as Woods made his way up the 72nd hole with an even more commanding lead: “It was dusk and I had sunglasses on because I had tears in my eyes. I knew he would do it,” Harmon said.

Comparison shopping of Woods’ career accomplishes nothing. He’s a Hall of Famer at least two times over, but the Harmon years stand above the others for the consistency and the drive and, mostly, for the dominance.